Prensa > Noticias y entrevistas

Noticias y entrevistas

Noticias sobre Arturo Pérez-Reverte y su obra. Entrevistas.

Arturo Pérez-Reverte: «War erases the capital letters from the big ideals»

Interview by Karina Sainz Borgo - zendalibros.com - 10/nov/2020 - 13/11/2024

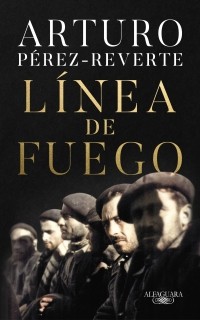

Ten days of combat between Republicans and Nationalists serve Arturo Pérez-Reverte to unfold an ambitious novel —a novel, it is a novel, he insists— about the Spanish Civil War. This is 'Line of Fire' (published in Spain by Alfaguara). Almost seven hundred pages in which the writer demystifies and humanizes the conflict. He changes his point of view and uses at least a dozen men and women to convey the complexity and simplicity that pushes human beings to confront each other.

People of different ideology, age, origin, opinions and state of mind intervene in a war in which many could not even choose their side, but they still fight for every inch of a small town. It is not a strategic territory, nor does it merit such firepower. And yet, they don't stop until they kill each other. Recreated within the context of the Battle of the Ebro, the assault on Castellets turns 'Line of Fire' into a fresco. In its pages there are anarchists, communists, requetés, legionnaires, nationalists, international brigade members, soldiers of the baby bottle replacements, war correspondents...

'Line of Fire' follows the path of 'Un día de cólera' (2007) and 'The Siege' (2010), because it weaves a work of multiple voices. Being a novel, Pérez-Reverte creates much more than that: it shows a choral defeat, a bitter confrontation. It all starts on the night of July 24, 1938, when 2,890 men and 18 women cross the Ebro River to take Castellets del Segre, a fictitious town that reproduces the pulse of one of the bloodiest battles of the Spanish 20th century.

The Spanish Civil War, the writer insists, was fierce and painful. They were not fighting for a strategic position and yet each of them fought until they killed the other or died. “I needed an emblematic battle, which was the summary of them all. The Ebro was the bloodiest of that war. There were 20,000 dead on both sides. It was the one that best reflected that bloody stubbornness. It was a clash of rams, very Spanish. That throwing the all meat on the grill, as the saying goes, to the slaughterhouse, both of them. It is a horror facing another horror”.

Throughout his 35-year literary career, Arturo Pérez-Reverte had not directly addressed the Spanish Civil War in his novels. Perhaps as a backdrop to a plot, or as a single episode, or a mere brushstroke, but not directly. He did it, as an educational children's book, in 2015, with a story about it told for young people. From there comes a thread that leads to 'Línea de fuego' (Alfaguara), a novel in whose 668 pages he narrates the conflict, and he does it as only he knows how to: without idealization, from the mud of the trenches, with the degree of detail of someone who has seen people die and fight. All of its protagonists have now died, and differently-intentioned versions of the war remain, which these characters refute.

In 'Line of Fire' the reader will feel the thirst, fear, desperation, hunger, pain, but also the courage (and cowardice) of those who fought more fiercely than those who, from the rear, ordered them to die. It is, as the editorial director of Alfaguara, Pilar Reyes, assured, a novel about war, a subject that Arturo Pérez-Reverte knows very closely: over 21 years (1973-1994) he covered 18 conflicts as a war correspondent, of which 7 were civil wars.

In the pages of 'Línea de fuego', characters that are "Revertian" to the core shine, such as Patricia "Pato" Monzón, a communications soldier from a republican unit made up only of women. She is nineteen years old, has a Tokarev on his belt and a backpack with heavy transmitters and cables that she will have to connect to the trenches. Pato left behind the Madrid life of dancing in Las Vistillas, but she does not forget the fascist bombings. Their certainties, sometimes monolithic, give in to the onslaught of a war in which everyone ends up as cannon fodder.

The point of view jumps from one trench to another, from humor to horror. Arturo Pérez-Reverte achieves this from a gallery of typically Reverte-like creatures: captain Juan Bascuñana, in command of the baby bottlers, a man whose words in capital letters have been taken away from him by war and who has under his command more than a hundred 17-year-old boys leaving home for the first time; also the soldier Ginés Gorguel, a carpenter from Albacete who was surprised by the uprising in Seville and now fights with the rebels, although always looking for a way to escape; Corporal Selimán, a memorable character, and the Regular troops of the Moroccan tabor... and with them dynamiters, republican soldiers, legionaries (Corporal Longines is a gem), the requetés with a picture of their "Moreneta" Virgin Mary on their Mauser and a "stop, bullet" talisman from the Sacred Heart on their shirt.

—You had addressed the Civil War before, but as a backdrop or short episode, except in 2015. Did 'The Civil War Told to Young People' lead you to 'Line of Fire'? Are they simultaneous?

—The Civil War was told to me by people who had participated in it. All of them have been dying and the human first-hand testimony has now disappeared. There is a divorce between real testimony and ideological discourse, which is being used politically. When I noticed it a few years ago, I was worried. That's why I wrote the Civil War book for young people. They are the ones who need not a new discourse, but rather to maintain the links between the two, because both are valid. Ideological discourse is not bad, but it needs to be contextualized with a human component.

—'Line of Fire' is, above all, a novel about war, the great theme of your oeuvre. You covered 18 of them in 21 years. What was it with you and war? What led you to it?

—War and I have a very intimate relationship, for many reasons. I am referring to war in general and the Spanish Civil War. It was recounted to me by my father and my grandfather, who, like another uncle of mine, were on the Republican side, and other relatives who were on the nationalist side. I know that part from their direct testimonies. On the other hand, I live the war because for years I covered it as a correspondent. With that war that I lived through on every trip and for 21 years, I completed the stories from my family and from my own reading. War is part of my intellectual furnishing, just as Proust or music for others. My mindset, or a part of it, was formed during war. When I see reality, I project war onto it. That's bad, because it makes me pessimistic, and good, because it makes me forward-thinking. It allows me to see and detect things that those who have not gone through that dramatic "school of lucidity" cannot see.

—'Line of Fire' seems like a great tapestry, a canvas like 'The Battle of San Romano' painting, but it is also a great choral defeat. Does everyone lose?

—No one who has been on a battle frontline is a winner. I have experienced both sides of the coin. In Eritrea I was a winner and in Croatia I was defeated. In 1977, at Tessenei, I was with the winners, and in Petrinja or Vukovar, in 1991, I was with the losers. I know what it feels like in both cases, when you advance forward or when you have to run for your life, and I assure you that there is no sense of triumph in either of the two. Not even when you win do you feel that you have won, even if the winner is able to plunder and keep the loot. I saw it clearly when they emptied and Eritrean bank. They had won, but there was no victory there. There was death, guys crying, misery... Nobody will say to you "I won the Battle of the Ebro." That is what war teaches: that there is never victory, not even for those who win. The Duke of Wellington said: "Aside from a battle lost, there is nothing more depressing than a battle won."

—The spirit of 1930s war correspondent Manuel Chaves Nogales runs through the book. The words of the prologue to his 'Blood and Fire' turn up in the mouth of 'Line of Fire' correspondent Phil Tabb.

—I needed an outside view of the Spanish, and I took advantage of the Phil Tabb character. He knows that whoever wins this war, Spain will have a dictator. That "chavesnogalian" vision is deliberately placed in his mouth, although it apparently comes from outside. There are several good novels about the war, but above all there are five very good ones, written by authors from both sides: Rafael García Serrano, Agustín de Foxá, Arturo Barea, Ramón J. Sender and Max Aub. And of course, the shadow of Manuel Chaves Nogales, who hovered over my book while I wrote it. Because he was the first to see the bloody drift from both sides.

—There is a tribute and also a criticism to the war correspondent. Vivian Szerman, the 'Vanity Fair' journalist, comes with a romantic idea, but everything falls apart around her.

—The war journalist has been mythologized, because he is a qualified tourist of war. I was one for 21 years and there is a universal truth: you go to war with a return plane ticket in your pocket. When you're done, you leave. And if things get really bad, you leave. I was not a combatant. I shared the misery and the danger, and yes, they could have killed me, and in fact they have killed many journalists who cover the war, some of them friends of mine, but in reality we are quite privileged: you can leave whenever you want, if they let you. The soldier cannot leave. It's like a sailor in a storm: you can't get off the boat. A journalist, no matter how involved he is and even if he takes risks, will always be a journalist, never a combatant. And therefore, he feels excluded from that space he occupies.

—Vivian goes to cover the International Brigades. She hopes to find heroes, but they are only soldiers who end up as cannon fodder. Does that demystify them too?

—They appear in the novel as they are leaving. It's a very interesting moment. They had arrived in Spain as bus drivers, manual workers, teachers, intellectuals, writers... Many with this romantic idea of Spain and the proletariat of the world. But once in battle they are cannon fodder. Many died. When you read their memoirs you realize the ideological destruction. That's what happens to Orwell: he was a Marxist POUM supporter who his own comrades wanted to kill. From there it is not so clear that there is a sharp division between good and bad. Some on the right might think: "The good ones are the ones on my side." Well, but among their own there were the Falangists, the Requetés, the volunteers by ideology or by profession. Someone on the left might think: "The good ones are on mine." Good, but within their own side there were communists, socialists and anarchists against each other. So, what is bad and good is no longer so clear. That on the one hand: ideological disillusionment. Then there is the fatigue on the other. When a soldier has been fighting for a long time there is physical decay. When he got somewhere, he could tell which ones had fought and which ones hadn't. And he was always right. You see it in the eyes, their facial expression. That's why I wanted to show the international brigades at that moment: when they already know that they are not going to win and they want to get out of there, to walk without being shot and to be able to have a beer back in Brooklyn.

Arturo Pérez-Reverte describes the weapons they used (Tokarev and Star pistols, Mausers, MP-28 submachine guns, Cintron hand bombs), the effects of artillery and crossfire from the walls, houses and bell towers. The reader can feel the shrapnel from grenades, the tanks, the aviation bombardments, the interminable assaults on the hills and the feared bayonet charges on the enemy's trenches and positions.

"I wanted that, when the reader had already read a hundred pages, he didn't care if someone was a legionnaire, a requeté, a communist... Because the important thing is the human being (...). A 15-year-old requeté is different outside the battlefield, not once inside it: they are all the same lives, destroyed by a war that no one won,” explains Pérez-Reverte.

Women are also important in this book. Although at the time of the Battle of the Ebro that 'Line of Fire' recreates they did not participate in the combat, the writer takes literary license to represent them through the Transmission Unit. «I did not want to portray a folklore militiawoman, but rather a well prepared, determined, methodical woman. They were the big losers of the war: in three years they saw a century of social conquests and freedoms disappear," he says.

It is a novel, its author insists. Not a manual, not a truth written on tablets. It is a cyclopean story, enhanced with the illustrations of Augusto Ferrer-Dalmau, an artist nicknamed "the painter of battles". This fiction arrives at a fertile moment in the carrer of Pérez-Reverte, who in the last four years has published six books: his series starring Franco-supporting spy Falcó, 'Los Perros Duros No Bailan' and 'Sidi', in addition to the history book 'Una Historia de España'.

'Line of Fire' eludes and crushes any catechism-style preaching, and Pérez-Reverte does so line by line: «It is a novel about us, about our memory. It's our story. It is not a novel that is foreign to us. It is not intended to reopen the latent conflict of the Civil War, but rather to make the reader recognize himself and his grandfather, his father, his relatives, and himself. And then, if you want to be more truly informed, not through my fiction but through reality, you should go look for a serious history book about the Ebro or Belchite, to find out what happened.

—Pato Monzón reminds one of the Montero brothers from the first Falcó adventure, only from the other side. She is brave, determined, idealistic, but she breaks down over those ten days...

—Because reality breaks people. When I first went to war, I did so with a romantic idea. But war was not that. It was crushed children, misery, crying women. I began to see familiar faces, that of my little sister, in the faces of the children. This rupture of big words in the face of dirty and concrete reality occurs in all cases. I doubt that an ideology will completely survive a war. I'm not saying they disappear, but they change. War is so brutal that nothing can resist it. It is an acid that corrodes everything, and erases your great words. Everyone who has been in war comes back with words written in lowercase words, not in capital letters. Honor, country, flag... you will never hear them from the mouth of someone who has been there. They are going to talk to you about the cigarette, the cold, the hunger, the friend, the thirst. That's what matters, and that I discovered. It's what led me to this novel.

—Even cowardice has its heroic moment in 'Line of Fire'. I tell you this because of the soldier Ginés Gorguel, who looks for a way to escape again and again, but always ends up back in combat.

—Bravery and cowardice in war are relative. There are people who act like heroes out of cowardice. Fear can make you fight, because if you don't fight they will kill you. If the fascists or the reds come here, they will kill you. And that's why they prefer to kill them first. That's what he thinks.

—The young Pardeiro, ensign in command of the legionnaires, does not see himself as capable of carrying on. He feels mutilated, dead, or on the way to being so. And yet it continues. What does this boy, forced to relieve his dead superiors, represent?

—There are many types of characters in war and in this novel. He accepts his fate: "I am here and I am going to do my duty." And what is that? If he is a soldier, then fight. You may not believe in the cause, but you do it. You don't fight for a flag or a country, you fight for a friend, because they can kill him or because if he leaves they will catch him. Or for being angry. War is fought for a thousand reasons, and because of all of them you can be a hero and a coward at the same time. They are not all the same reasons, each has their own. Why does the Moor Selimán fight? He likes it, they give him money, oil, and Saint Franco, as he says, kills the communists who burn churches and mosques. That's why he repeats so much that he will go after the "abastards," as he calls them. He is one of the most colorful characters in the novel.

—Corporal Selimán, the boy Tonet, or even that ceasefire so that a woman can give birth, add humor and tenderness to the book.

—This novel is very Spanish. It has that bad-tempered, complicit humor of singing a couplet to those in the other trench on the other side, and they are real lyrics. It's about that fatalistic, resigned sense of humor, as a defense against what you have coming your way.

—When he sees those on the Republican side fleeing, now defenseless, a character deliberately jams his weapon. The order is to shoot, but deep down he doesn't want to.

—Humanity is not at odds with cruelty. In the morning you can be killing the enemy in the heat of combat and in the afternoon spare his life. The human being is not monolithic, he is multifaceted. I have seen many atrocities of all kinds in my career. I have seen many heroic people do atrocious things and how good, loyal, supportive people arojund a fire at night, and then in the morning, for very complex reasons, do different things. The world is a very son of a bitch place, and in war even more so. There are words that temper all that: dignity, compassion, loyalty, dignity. Human beings have all of that inside, and war brings out the best and the worst. And that was what I wanted to show in the novel. That character, who has fought for days, asks himself: "Why am I going to kill him now, if it is already unnecessary?" "Now that no one is watching, I can allow myself to be compassionate." That is the human being.

—Bascuñana is a typically Revertian character. “The truth is not always revolutionary,” he tells Pato. There is attraction between the two, yes. Deep down, he is the voice of what will happen to the young communications soldier?

—He is her on the other side, when she goes through the barrier. And she will. In fact, Pato never returns to Spain. Something has broken inside her. She goes to war thinking one thing. But war corrodes everything.

—Today the world is not capable of separating an author from his work. Does a writer really have to explain what he or she writes? Why?

—Because this is such a ridiculous world, in which you have to explain why a novel is a novel. It is very sad and almost exhausting to have to explain that Nabokov is just writing a novel, and that Céline is also telling a story, that 'Pascual Duarte' is a novel. The author does not even have the obligation to reflect himself truly. Is everything that is said in 'Line of Fire' linked to me? Do I share the behaviors of all of the characters? Don't be ridiculous! Don't judge me because of my characters! If I make a novel about an unscrupulous rapist or a murderer, that does not mean I defend or support rapists and murderers. Even that has to be explained. It didn't use to be necessary. A novel is an artifact that you launch into the world, so that people get things from it. It is very sad to see a writer justifying his novels. That's exhausting, and it's what I'm never going to do.

—What influence does Joseph Conrad have in this novel and in your work overall?

—Conrad is the sea, the adventure, the men subjected to tests and living under pressure. He is the author that remains standing for me. Just as Bascuñana loses its capital letters in the war, I have lost great authors, classics that were fundamental when I was twenty years old. I don't reject them, it's just that at one point in my life they were fundamental and now they are not so fundamental for me as a reader. Now I read Scott Fitzgerald or Dumas, which I have quoted dozens of times in my life, and I no longer find anything new in them, nothing that feeds me the narrative nourishment I need to work. It's like visiting old relatives who have already told you about their lives many times. But I'm reading Conrad for the umpteenth time and I'm still moved. Conrad makes me think, I like writing novels under his influence. It's a little more complex than that, because I have my own world, but he is there. In fact, he's the only writer I have a photo of at my work space. When they tell me that now I physically look like Conrad, with the droopy eyes and the beard, it makes me excited! —laughs— I'm not comparing myself, far from it. What I'm trying to explain is that Conrad is my guardian angel.

—In what do 'The Painter of Battles' and 'Line of Fire' coincide?

—'The Painter of Battles' was a much more about intellectualised war, and this one is more direct and stark. I want the reader to come to war with me. Do you want to know what happened to your grandfather or your father or your uncle? Come. Here, find out. Once you are there, try to start saying this is good and this is bad, try to start drawing red and white lines. From the outside everything is very clear. It is very clear: legitimate republican side, illegitimate Francoist side. But when you approach war as a 17-year-old, whether you are a communist, anarchist, socialist or requeté... do you really believe that at that age there is a human difference between them? Do you think their half-baked ideas weigh more on them than their youth, the misery and the human drama they are experiencing? I have seen boys of that age fight and I assure you that they all operate with the same instincts of aggression and survival. It is also true that war is never observed globally by a soldier, but only through the small portion of it that you see with your own eyes. I didn't want the reader to go through the novel with an omniscient narrator, but rather from the fragments, the small details, the confusion, how a character actually sees the war. That's why I use so many.

—It is also a novel that gun lovers and collectors will enjoy. Did the Republicans have worse weaponry and military strategy?

—At this time, Franco's equipment was already much more effective and overwhelming, although the Reds had better tanks, better fighters, but overall the national technical superiority was obvious. But there is another thing, which is fundamental, and becomes clear in the novel: discipline. This is what Gambo, the communist battalion commander, says, lamenting that the Republican army is often chaos, while the enemies are often very efficient. That organization and that discipline was what made the nationalists prevail in the war. Both sides fought with great courage and determination. There was no difference there. Nor was it the material that made the winning side prevail. The difference is that the nationalists, tightly disciplined by a military hierarchy, had a single objective: to win the war, to exterminate the adversary. The Republicans had many aims at once, like the revolution of the proletariat, fucking the anarchists or communists, etc. Their energies, instead of concentrating on beating the nationalists, were often wasted on fighting each other. It was impossible for them to win that war.